Replacement Turtles

Pamela Ramos Langley | Terri Kelleher

Young Lilly was a straight standing, chin out-thrust, full-faced smiling sort of kid. She had a way with fashioning effects and tallied an impressive track record of positive outcomes resulting from her capabilities. For instance, when she lost the petite shoes off her favored Barbie, she had only to focus on where she’d been that morning to find one on the front porch, the other by the toilet. She was able to reverse her mother’s impulse to make tuna casserole by relating instead how much she loved her ham mac n’ cheese, and the ways it seemed to improve her math test scores.

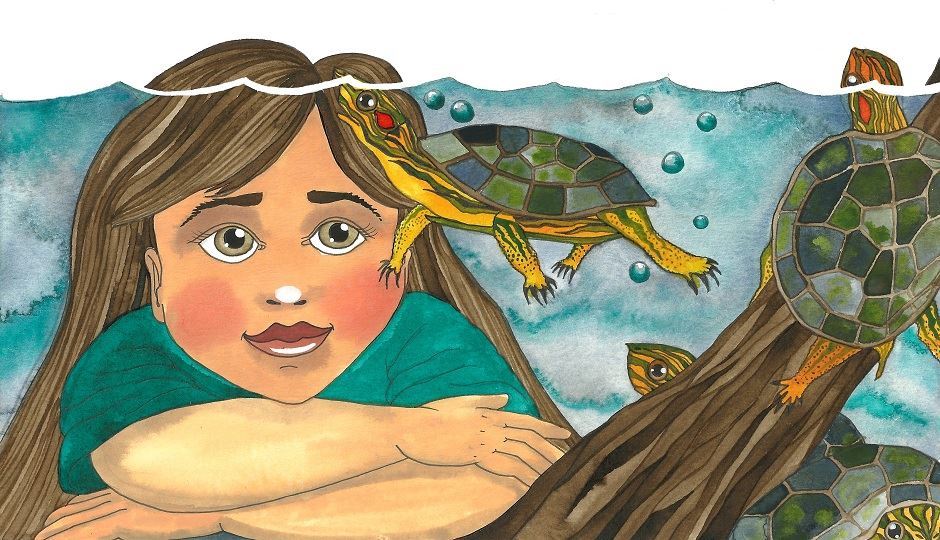

Things weren’t always so peaceful at home, but they weren’t so bad either. She didn’t get a pony when she requested one, but that same day her mother drove her down Sepulveda Boulevard to The Pet Stop, where they purchased a quartet of pea-green, orange-cheeked turtles. Lilly pointed out which ones she preferred to the shop worker who plucked them from a massive tank where they clustered and bobbled like paddle boats. He suggested an acrylic habitat with molded sections sure to spark reptilian interest, and her mother grabbed a bag of assorted-color tank pebbles.

At home they set the bowl on Lilly’s desk and poured in the flashy pebbles. They filled it in the bathtub and added drops to condition the water. Her mother handed Lilly a canister of food flakes and explained how to feed the turtles. Lilly assigned names on impulse: Penelope, because she liked the way the word tripped off her tongue, Jeremiah because she admired prophets, Ted because it felt solid, and Nancy after her favorite sitter.

Initially the turtles thrived, enjoying the various enrichments that Lilly added to the tank. But after a couple of weeks and despite the drops, the water turned murky. Her mom helped her clean the habitat, but the sludge crept back. The turtles grew listless, alternately developing a suffocating membrane over their heads, as though they were being Saran-wrapped for later unpacking. But Lilly silently advocated for the ailing turtles each night in bed, and—never witnessing a death—believed her efforts succeeded when the membrane vanished and the turtles rallied.

When asked by teachers, other adults, and an assessment specialist who determined Lilly to be above-average intelligence with keen cognitive skills, Lilly enthused that she held great hope for her future. She told the assessment specialist that she suspected that she was able, if not to wholly manifest her prospects, to influence and master the outcomes.

“I’m an optimist,” she shared.

“I admire your confidence, Lilly,” said the specialist.

“Well, I can tell you that I have a certain gift,” Lilly beamed.

“What gift is that?” the assessor asked.

“I’m able to fix things with my mind. Like I can save my turtles when they’re sick, or when I’ve lost something, I close my eyes and can map out how to find it! And when my mom and dad fight, I get between them and think about peace and they almost always stop yelling at each other.”

“That’s excellent, Lilly,” said the specialist. And after a pause she asked, “Do your parents fight very often?”

“Sometimes,” she said,” but I fix it.”

The specialist cautioned that some things are beyond our control. But she encouraged Lilly to always visualize positives as simple as lost items, or as vital as improving outcomes.

***

Lilly had adored Vincent since he was introduced as the new kid in class. She felt an instinct prompted by his dingy jacket, shabby at the seams and short in the arms. She shadowed him as he rounded the playground, pretending to search for insects or demonstrating her skill at hopscotch while looking to see if he was watching. One afternoon, aggravated by her unearned devotion, Vincent informed her that she had a flat face and skinny legs. She was hurt, but took a solid minute chewing at her options before she replied, “That’s not true, Vincent. I’m very pretty.” To which Vincent, who had it rough at home, said in a tone that rattled her faith, “You’re not pretty at all, Lilly. At all. And you’re weird. Stop following me.”

Lilly stopped following him, but remembered what the specialist suggested and over the next few days visualized Vincent being nicer to her. And it did seem that with his personal space regained, he curbed further insults.

***

A few days after the Vincent incident, Lilly found her mother in her room reaching into the turtle bowl. She knelt on a stool with her back to Lilly, clasping a wriggling turtle. On Lilly’s desk was a Ziploc bag containing Ted, his neck dangling, gaze fixed to eternity through an opaque sheath. Lilly heard a faint splash, and watched the new turtle listing left and right, splayed feet adjusting in the span of limpid water. Displaced pebbles settled like confetti in a snow globe. She asked her mother what she was doing, and her mother turned and exhaled, wiping boggy hands on her black lycra leggings.

“Lilly, I’m sorry, but while you were at school Ted died.”

“He did? What made him die?”

Lilly couldn’t reconcile her efforts against destiny.

Her mother rested her palm on the cap of Lilly’s tender shoulder, “I don’t know exactly, love. Lots of your turtles have died. That one wasn’t even the original Ted. The turtle crawling into the water there—” she gestured, “Nancy is it?—isn’t Nancy number one, either. They get a disease and I can’t take turtles to the vet. So I bought you new ones instead.”

Lilly remembered previous turtles that were filmy and dismal one day, then verdant and robust the next. She had believed that she was healing them by concentrating on that desire. Now she realized there may have been six Teds, four Jeremiah’s and a couple of Nancys; she’d never know.

“Maybe they need different names,” Lilly decided, “let’s call this new one Vincent.”

When her mom left with the bag containing dead Ted, Lilly sat alone in her room with the turtles. They blinked at her mammoth eyes through the acrylic and raced away from her grasping hand. She caught Vincent and held him in her palm, stroking his spine and noting some flaking on his moss-green shell. Upon her touch he stiffened and thrust his legs into squeeze-box pockets. His tail whipped right, tucking away.

***

Lilly was thrilled to learn that Vincent was enrolled in the same day camp session as she was that summer. She convinced her mother to drop her off early, but Vincent was already there, slumped in a corner behind the lunch-box cubicles. She tried to rekindle their one-sided friendship. But Vincent’s dad had left the family, and the boy arrived each morning with smudged eyes and unspent anger that Lilly received. Lilly sought him out during a recreation break and told him about using his mind to fix his world and how it most often worked for her. He’d taken to gripping his arms across his chest as if it were winter. His fingernails dug into his arms.

“Lilly, can I ask you one thing and you’ll do it?

“Uh, huh,” she waited for his direction.

“Can you please shut up? Just … shut up.”

***

The new turtle Vincent didn’t last much longer than the others who, one by one, had died. She found him upside down in the water—victim of the same Vitamin A deficiency caused by poor grade commercial food (she later learned) that had snuffed her previous friends. After a rough summer of loss, he’d been the last of the bunch to go.

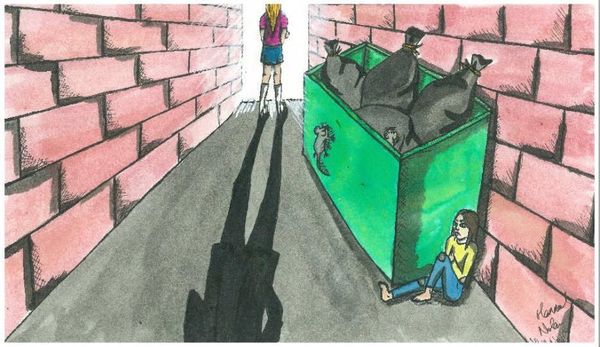

She contemplated Vincent floating aimlessly in the swampy water. The August heat intensified through her bedroom picture window. She turned to seek out her mother, but at her doorway angry adult voices rumbled along the oak floorboards. Instead she padded to the kitchen, dampened three sheets of Brawny super-absorbent paper towels and shrouded Vincent with them. She plopped the bundle into a sandwich bag, dumped the turtle water, and carried the corpse and bowl, wet pebbles still clinging to the sides, out to the garbage bin. She hoisted the monstrous lid back exposing the week’s bulging trash. From inside the house she could hear her parents’ increasing strife.

She closed her eyes for just an instant and then opened them again. She rubbed the lids with her knuckles to dispel the cloudiness. The stench of the trash overwhelmed her. In went the bowl containing the bag with Vincent; barely making a thud, and she closed the lid.